|

|

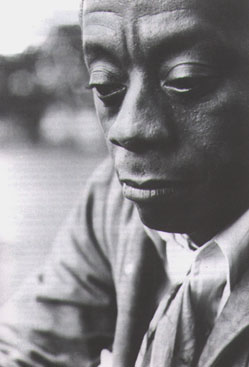

by James

Baldwin

The first line written in The

Amen Comer is now Margaret's line in the Third Act: 'It's an

awful thing to think about, the way love never dies!' That

line, of course, says a great deal about me - but I was

thinking not only, not merely, about their terrifying

desolation of my private life but about the great burdens

carried by my father. I was old enough by now, at last, to

recognize the nature of the dues he had aid, old enough to

wonder if I could possibly have paid them, old enough, at

last, at last, to know that I had loved him and had wanted

him to love me. I could see that the nature of the battle we

had fought had been dictated by the fact that our

temperaments were so fatally the same: neither of us could

bend. And when I began to think about what had happened to

him, I began to see why he was so terrified of what was

surely going to happen to me.

The Amen Corner comes somewhere

out of that. For to think about my father meant that I had

also to think about my mother and the stratagems she was

forced to use to save her children from the destruction

awaiting them just outside her door. It is because I know

what Sister Margaret goes through, and what her male child

is menaced by, that I became so unmanageable when people ask

me to confirm their hope that there has been progress - what

a word! - in white-black relations. there has certainly not

been enough progress to solve Sister Margaret's dilemma: how

to treat her husband and her son as men and at the same time

to protect them from the bloody consequences of trying to be

a man in this society. No one yet knows, or is in the least

prepared to speculate on, how high a bill we will yet have

to pay for what we have done to Negro men and women. She is

in the church because her society has left her no other

place to go. Her sense of reality is dictated by the

society's assumption, which also becomes her own, of her

inferiority. Her need for human affirmation, and also for

vengeance, expresses itself in her merciless piety; and her

love, which is real but which is also at he mercy of her

genuine and absolutely justifiable terror, turns her into a

tyrannical matriarch. in all of this, of course, she loses

her old self - the fiery, fast-talking little black woman

whom Luke loved. Her triumph, which is also, if I may say

so, the historical triumph of the Negro people in this

country, is that she sees this finally and accepts it, and,

although she has lost everything, also gains the keys to the

kingdom. the kingdom is love, and love is selfless, although

only the self can lead one there. She gains

herself.

One last thing: concerning my

theatrical ambitions, and my cunning or dishonesty - I was

armed, I knew, in attempting to write the play, by the fact

that I was born in the church. I knew that out of the ritual

of the church, historically speaking, comes the act of the

theatre, the communion which is the theatre. And I knew that

what I wanted to do in the theatre was to recreate moments I

remembered as a boy preacher, to involve the people, even

against their will, to shake them up, and, hopefully, to

change them. I knew that an unknown black writer could not

possibly hope to achieve this forum. I did not want to enter

the theatre on the theatre's terms, but on mine. And so I

waited. And the fact that The Amen Comer took ten years to

reach the professional stage says a great deal more about

the American theatre than it says about this author. The

American Negro really is a part of this country, and on the

day we face this fact, and not before that day, we will

become a nation and possibly a great one.

Circa 1954

|