PREVIOUS ISSUES | WEB LINKS PAGE | READER'S COMMENTS | BACK TO FLAME ARCHIVE HOME |INDEX OF ISSUES 1-10

PREVIOUS ISSUES | WEB LINKS PAGE | READER'S COMMENTS | BACK TO FLAME ARCHIVE HOME |INDEX OF ISSUES 1-10

Co-editors: Seán Mac Mathúna • John Heathcote

Consulting editor: Themistocles Hoetis

Field Correspondent: Allen Houglande-mail: thefantompowa@fantompowa.org

The

Tibetan Government-in-exile An

Annotated Chronology of Tibet in the 20th Century

Bicycle

trip over the Himalayas Tibetan

Cultural Region Weblink Directory It was the 26th

March 1986 and a Full Moon was due. I had arrived in Nepal

two days earlier from India after spending almost three

months in the country. During the afternoon, I was sitting

on the steps of a Shiva temple in Durbar Square, near of old

royal palace in the centre of Kathmandu with my friends Lee

and Chris, when a middle-aged American approached us and

asked "You guys feel like going to Tibet?". We asked what

the details were, and he told us he could arrange it for

$50. We said we would think about it, as going to Tibet,

which we thought then was a closed country under Chinese

occupation, had not been on our original travel plans when

we had left England in December 1985. I didn't have that

much money, and initially, l was not into the idea. Along

with my two other travel companions, we banged our heads

together and decided that we just had the money to get there

and back. Tibet had only

been open to foreign travellers since 1984, and the route

over the Himalayas via the village of Tatopani had only been

clear for travellers to cross into Tibet, since the

beginning of 1985. So we would be some of the first

backpackers to be lucky enough to get there. We had a

feeling that we would not have a easy time: We had heard

that the Chinese policy on individual tourism in Tibet

seemed to be one of extorting as much cash as possible from

travellers - but no so much as to scare them off. Before very

long, we had taken it one step further: we would go to the

Pakistani embassy in Kathmandu and get visas: We had decided

to go into Tibet, then cross into China and come back to

India via the Karakorum highway in the Pakistani part of

northern Kashmir. I personally knew that this was an

ambitious plan considering my lack of funds. Anyway, we

decided to go to a hotel in the north of Kathmandu and hand

over our passports to these dodgy American's who were

obviously doing some kind of deal with corrupt officials in

the Chinese embassy (It was our understanding that you could

not get a visa for Tibet in Nepal). We decided to go for it.

In the meantime there was a really nice hill station outside

Kathmandu called Nagarkot, which was said to have panoramic

views of the Himalayan mountain range on a clear day,

including Mount Everest (known by the Nepalese as

Sagarmartha or Brow of the Ocean). We decided to spend a few

days there, leaving Kathmandu by bus on April 1st for the

short journey to Nagarkot. We ended up

spending two days there - it was really cold, but it gave us

a taste of what to expect in Tibet. Its not a village or

anything (the area was first developed as an army base), but

more a collection of guest houses and hotels that stretch

along a cultivated ridge for a couple of miles at 6,397 ft

(1950 m). One morning we did get up and we saw the Himalayan

mountains for stretching as far as the eye could see,

including Mount Everest. We all felt very excited about

travelling through the Himalayas to Tibet. The visas were

sorted out by the Chinese embassy on April 7th. When we went

to pick them up, someone who spoke Chinese, claimed they

indicated we were going into Tibet at a completely different

point to the one stated in the visa. We then went to

the Pakistani embassy and collected visas for for the trip

through Kashmir. Initially, we were planning to go a

difficult route from Tibet to China and into Pakistan, along

a road that follows the Himalayan mountain range via the

holy Mount Kailesh, which is roughly where Nepal, India and

Tibet meet. Hindus believe the God Shiva lives there. It it

also a major pilgrimage centre for Hindus and Buddhists. As

Asia's most sacred mountain, Tibetans revere Mount Kailesh.

It stands completely alone with no other peaks near it.

Pilgrims travel to this remote area in far western Tibet to

complete the circuit around the base of this sacred mountain

(to do so is said to erase the sins of a lifetime), and to

the holy Manasarovar Lake. The four great rivers of Tibet,

India and Nepal have their origins near Kailesh; the

Tibetans consider these rivers and their sources sacred. As

we were walking out of the Pakistani embassy, we bumped into

the ambassador, who laughed when we told him of our route to

Pakistan. "You'll never make it" he warned, "there's very

few people who live there, let alone means of transport or

food". We were later to find out he was right, which was

confirmed when we arrived in the village of Lhatse, on the

way to Shigatse in Tibet. The only way to travel along that

route is in the back of lorries - and then you don't know

how far the lorry is going. And if they leave you in the

middle of nowhere, it might be days - or longer - before

another lorry comes along. There are no hotels or shops, it

it was clear that not only was it virtually impossible to do

the journey, any attempt could easily lead to a

life-or-death situation. We quickly abandoned the idea and

settled on making our way to the Tibetan capital,

Lhasa. The best way to

get there was by bus from Kathmandu up to a village called

Tatopani, which means "Hot Water" in Nepali. It is the most

famous hot water spring in Nepal, situated right across the

border between Nepal and Tibet at the end of the Arniko

Highway. The road was built originally by the Chinese - must

to India's distress - in the 1950's. We left

Kathmandu at 5 am on April 18th 1986 and caught the 8-hour

bus to Tatopani, arriving early one evening. We decided to

get acclimatised here as it just short of the Tibetan

crossing. Kathmandu is at 4291 ft (1500 m) above sea level,

with Tatopani at 5019 ft (1530 m). However, before you get

to Lhasa at 11,811 ft (3600 m), you have to cross the Lhakpa

La pass which is at 17,126 ft (5220 m). We had heard

stories of people being struck down with altitude sickness

because they attempted these journeys to soon, so we decided

to take it easy. This illness is known as Acute Mountain

Sickness (AMS) and you are likely to be affected by this as

you pass over between 11,000 feet (3400m) and 13,700 ft

(4200 m). For travellers to Tibet, this includes the section

of the road after Nyalam, and the Khama mountain pass before

Lhasa. Thus, we spent about five days in Tatopani, exploring

the surrounding mountains during the day, including the

Shiva temple in a cave across the Bhote Kosi river from

Tatopani, and chilling out in the evenings. I read somewhere

later that it was the deepest gorge on earth. This l can

certainly believe, as it is surrounded by some of the

tallest mountain peaks of the Himalayas, including Mount

Shisha Panma at 26,398 ft (8046m). The first place

we stayed in was a Nepalese house, with a goat in the

downstairs room and chickens in the rafters above us in the

room where we slept. We went to bed laughing about whether

the chickens would drop their crap on us whilst we slept.

They didn't. It later turned out that the mice attacked our

rucksacks, succeeding in making about four holes in mine -

drawn by the cheese, bread and muesli in the bottom of

it. Tatopani is a

very nice village, but very cold at night. The worse part of

the night would be having to go down the stairs into a dark

room (containing the goat), and make you way to a door which

led to the top of the river bank. There is no sewage system

in Nepal, so every village and town that has a river uses it

basically, as a toilet (hence, the risks of hepatitis etc).

I had seen people using the Bagmati River in Kathmandu

either as a place to wash or as a toilet. We were advised

again and again by travellers never to drink water from

rivers in the mountains, unless you are on ground high

enough to know that there are no villages above you.

The hot-water

springs in Tatopani are down a narrow footpath near the

river. Here you could wash as much as you liked - when you

liked. It was nice first thing in the morning to have a long

hot wash with the other villagers, some of whom would also

be washing their clothes there. The waters there were said

to have healing properties. I once saw a Tibetan monk at the

springs washing a leg with what looked like some form of

dermatitis on it. It was certainly the first place that l

had seen cannabis growing everywhere - by the sides of the

roads, and everywhere up in the hills, and when we down at

the springs one day, a local Nepalese man pointed out this

fact and exhorted us to smoke it. But, it wasn't the sort

that was good enough to smoke, so we didn't bother.

Knowing that we

were going to a very cold country, neither of us had

sleeping bags - who needs to take one to India or Nepal

unless you are trekking ? We had met someone who had told us

that a silk sleeping bag within a proper one would keep us

warm. So we took this advice, and bought the silk in a

market in Kathmandu, then took it to a sowing shop, where

the sleeping bag was quickly made for about 10 rupees.

Cheaper than buying a sleeping bag, it kept us warm in

Tatopani, which was very cold at night, compared to the

humidity of Kathmandu. As something very cheap and

practical, l would advise anyone who travelling to Tibet to

get one made when they get there - especially if you arrive

in Kathmandu first. We knew that

food would be short, so we bought some muesli and cheese and

some other basic food stuffs to keep us tied over. We had

also heard in advance from other travellers not to expect to

get regular food supplies in this part of Nepal or Tibet. We

had no maps (although l did buy a Tibetan phrase book in

Kathmandu), little money, and no knowledge of Tibet. I

didn't know what to expect when we left Tatopani and crossed

the border. The food was awful in Tatopani, the only basic

foodstuff available was an omelette or dahl bhat. We

all seemed to be losing weight quickly ! I did meet two

interesting people in the village though. I was walking out

of a cafe after just eating my omelette, and there walking

up the road towards the border post were two Tibetan monks

and a Nepalese man. Seeing they were very friendly l

approached them with the Nepalese greeting Namaste !

The Nepalese man explained to me that one of the monks was a

Rinpoche (Precious One), an incarnation of a famous

monk. He was a Lama of a Monastery (or Gompa)

secretly returning to organise people and guide his monks

living under Chinese occupation. I wished him well, as l

knew that he was risking his life simply by spreading the

word of Tibet's leader, the Dalai Lama, through the

monastery. Meeting the

Lama in Tatopani made me realise how little l knew about the

political situation in Tibet. However, being reasonably

knowledgeable on history (the only subject l ever did well

at school), l had a basic outline of Chinese rule in Tibet.

I had long been interested in Buddhism, ever since my friend

Tom Spiers, gave me the book The Dhamapada in 1983,

which left a profound impression on me. Apart from that, the

closest books had come to reading about Tibet and its people

was when l came across Magic and Mystery in Tibet by

Alexandra

David-Neel

(Unwin Books, London, England, 1965). She was the first

European woman to travel to Tibet in the 1920's, and she had

met the 13th Dalai Lama in Sikkim whilst he was there on a

state visit. He encouraged her to learn Tibetan first, and

after studying it, she became a Buddhist, and later a Lama.

Her book is now recognised as a classic and a unique insight

into the Tibetan people before the Chinese invasion. I had

also read The Bardo Thödol (The Tibetan Book of

the Dead) which was originally translated by Lama Kazi

Dawa-Samdup and edited by W. Y. Evans-Wentz (Oxford

University Press, London, England, 1927). Dawa-Samdup had

also met David-Neel when she first travelled to Sikkim in

the 1920's. What l was to

see in Tibet, after leaving Tatopani, shocked me and my

friends - the destroyed monasteries, the smashed culture,

and the widespread colonial settlements of Han Chinese,

whose population is now said to be bigger than the

indigenous Tibetans. As there is a large Tibetan population

in Kathmandu, its quite easy to find out, and see the

consequences of the Chinese occupation, with over a 100,000

Tibetans living in exile. Thus, from this point of view,

Lee, Chris and myself were very fortunate in being some of

the first Western backpackers to Tibet in 1986, as noted by

Chris Taylor in Lonely Planet guide to Tibet

(1995): Tibet lost its

independence in the last century - first, it was invaded by

Britain in 1903, and after the British withdrew, it enjoyed

independence until it was invaded and annexed by China in

1950. The Chinese Communists claimed it as an ancient

province, and justified their actions by saying that it was

"saving" Tibet from feudalism. Thus, when the Chinese army

invaded Tibet on 7th October 1950, the Tibetan army, a

poorly equipped army of some 4000 soldiers, was in no

position to resist a force of some 30,000 Chinese troops,

who attacked Tibet from six different directions. Neither

India or Britain - traditional friends of Tibet - opposed

the Chinese invasion; in fact, shamefully, they convinced

the United Nations (UN) not to debate to issue at all for

fear of incurring China's wrath. Only the CIA

provided covert help to Tibetans eager to take up arms

against Chinese rule. But this was because the CIA also

supported the nationalist Chinese forces based in Burma and

Taiwan, as part of its secret covert war against Communist

China in the late 1940's. From bases in Nepal, the CIA

provided radio transmitters and arms to armed resistance

groups who would later be ruthlessly crushed by the Chinese

army. When the Dalai Lama had been forced to flee Lhasa

(disguised as a soldier) on 17th March 1959, the CIA sent in

agents to help get him out, who included the son of the

famous writer Edgar Allan Poe. With their help, the Dalai

Lama and his entourage made it safely across the border into

India. I met a Tibetan

in Nagarkot who claimed that when the Dalai Lama fled from

the Norbulingka Summer Palace, he was hit by Chinese bullets

- which just bounced off him. In fact, although l found out

later, that no such incident had happened, it indicated to

me that Tibetans believed that the Dalai Lama was protected

by magical powers. In fact, l have heard it said that some

Tibetans believe that Tibet's karma was bad and that's why

China invaded the country in 1950. Apparently, this had been

foretold by bad omens (such as a earthquake) and other

prophecies (similar statements were made at the time of the

uprising in Lhasa in 1989). I have also heard the argument

that if China had not invaded Tibet, then a significant

number of Tibetans would not have been sent into exile, and

thus help spread the message of the Buddha to the world, all

of which l can believe. The Lonely

Planet guide to Tibet - which l was pleased to see takes

a healthy stand against Chinese rule - was handy to check

background information on some of the places l visited. It

also describes the Chinese occupation as the "worst

misfortune the inhabitants the 'Land of the Snow' have been

forced to endure". In the last fifty years or so, it is

estimated that as many as 1.2 million Tibetans have died as

a result of the Chinese "liberation" - many of them (notably

monks), executed or dying of hunger in concentration camps.

Some 100,000 ended up in forced

labour camps

- the alleged source today of many of China's manufactured

exports. Furthermore, some two-thirds of Tibet were absorbed

into China, notably the northern Amdo province, which was

the birthplace of the present 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. The

number of monasteries in Tibet was reduced from 6254 to

around 10 - many of them looted and destroyed by the Chinese

army. This l could believe, as l saw with my own eyes as we

drove from Nyalam to Shigatse (and along the road to Lhasa)

many ruined monastery's and forts (Dzong's) on distant

hilltops. I kept a diary

every day when l was in Tibet, and when it came to writing

this story of my journey there, l bought a couple a books on

Tibet to get some more background information to include.

Once again, the Internet proved invaluable: Not only was l

able to check a multitude of sites dealing with travel to

Tibet (including overpriced bicycle trips), it has been the

main source of pictures used in this essay (as l didn't take

a camera to Tibet). I also checked out websites dealing with

Chinese repression in Tibet - Amnesty

International,

Human

Rights Watch,

the

Tibetan government-in-exile,

International

Commission of Jurists,

and most of the official Chinese government websites, which

all give a completely distorted version of Tibetan history.

Much of what l read in the Lonely Planet guide to

Tibet: Thus, on April

23rd, we left Tatopani on small bus crammed with people and

totally overloaded, and made our way up into the clouds to

Tibet. The next stop is a couple of miles up the road at

Kodari, where the Nepalese customs post is. After having our

passports checked, the bus made it's slow journey up to the

so-called "friendship bridge" over the Bhote Kosi river that

divides Nepal and Tibet, and begun the long journey to the

Chinese controlled Tibetan Customs post about five miles up

at Khasa (Zhangmu). The view as we

got higher was amazing, the further we drove up the road,

the more nervous l got - especially when l noticed that the

road - which is taken away on regular basis by landslides -

was nothing more than just a mud-track. Eventually, we

turned a corner to be confronted by armed soldiers and a

banner that declared "Welcome to the People's Republic of

China". The bus came to an abrupt halt and we were taken out

and into a Customs hall, surrounded by smiling Chinese

officials to have our bags checked. They didn't really check

them. They just looked inside our rucksacks, like they were

in a hurry and then smiled at us and they passed them back.

Maybe there's a bus leaving in a minute l thought. There

wasn't. I noticed that all the Tibetans on the bus had been

taken to one side, as the three of us had out bags checked.

When we came out, l saw that all the baggage belonging to

the Tibetans was piled up on the side of the road. You could

tell they were going to be there for hours. We were in

Khasa, a small village perched on the side of the road that

goes through the Himalayas. But where to stay ? and how do

we get out of this place to Lhasa ? We had heard that there

was at least one bus a day going to Shigatse, the nearest

Tibetan town - but how do we catch it ? None of the Chinese

seemed friendly and if any of them spoke English, they

didn't to us. We noticed that there were Chinese men -

possibly businessmen - driving range rovers out of the

village towards Shigatse. We decided that the only way the

three of us were going to get out of this place was to just

hire one of these cars, and then pay what we thought was a

fair fare in cash at the other end. My own

experience in India had shown me that if you roughly know

the price of something, sometimes just pay and walk off -

especially if you have little money. You just can't afford

to pay the sort of prices that some people demand,

especially when then refuse to barter with you. Generally

speaking, l only really came across this in Tibet. The

Chinese were the worst. We did try asking a couple of range

rover drivers how much it would cost to drive to Shigatse

and the prices they quoted us were just outrageous. So we

decided to book a room and go on the attack in the next

couple of days. The following

day, l saw for the first time, a mountain bike. I was a keen

cyclist long before l went away to India in 1985. We were

walking around Khasa one afternoon when we came across these

four Americans pulled up along the side of the road, one of

them, l think, had a puncture. I got talking to a Chinese or

Japanese American who said his name was "Robert". I was

amazed to see cyclists at this height making the hazardous

journey across the Himalayas. I asked him why they were

doing it, and he told me that they were being sponsored by

the National

Geographic

magazine to go into Tibet and take pictures. I didn't think

about it at the time, but later, after meeting "Robert"

again in Lhasa on May 30th, l thought to myself, how good a

cover that would be for CIA agents getting into

Tibet. The following

morning on April 25th 1986, we got up and managed to hire

the first range rover we saw. We didn't bother asking about

how much it would cost, we just piled in and told the

Chinese driver one word: "Shigatse". It would be a two day

journey to the second biggest in Tibet. From Khasa to Lhasa

it is 520 miles (837 km), and a journey that can take up to

four days. The next place along from Khasa is a another

village called Nyalam which is at 12,467 ft (3800 m), where

the temperature really drops. I already knew that nearby

(some 10 miles or so) was a temple associated with Milarepa,

the famous Buddhist mystic and song writer, who lived in the

late 11th and early 12th centuries. But there would be no

time to visit it, although l saw it in the distance on the

way back to Nyalam later. After arriving,

we were taken to what seemed like a prefabricated hut (l

think it was a hotel for truckers), and given a room with

three beds for the night. Before we left the driver, he

indicated by pointing at his watch and making gestures with

his fingers, that we would up early the next morning at

around 4/5 am for the journey to Shigatse. The room had

one broken window at the end of it, and l remember looking

out through it after dusk and seeing the snow falling down,

and for the first time Tibetan nomads with their Yak herds

grazing outside the tents where they were living. I was

amazed that nomads could live at this altitude, but then

again, as l was to find out, the Tibetans are a hardy

people. In our room, the beds had two huge duvet's, under

which we slept almost fully clothed in our silk sleeping

bags. Our bodies shaking, we crashed out. It seemed that

l had only just shut my eyes when there was a loud banging

on the door. It was still pitch black, but when we looked at

our watches it was about four-thirty in the morning. We got

up and made our way bleary eyed to the range rover. As we

drove out of Nyalam we seemed to started leaving the

Himalayas behind us. Up ahead was the Lalung Leh pass which

is at 16,569 ft (5050 m) high, followed by the Lhakpa La

pass at 17,126 ft (5220 m). We got there after a few hours.

After driving

for hours upwards you suddenly come up to the pass and cross

over onto a large flat plateau, known as the Lhakpa La pass.

Here we saw the first Tibetan prayer flags and small

Chörten's (or Stupa's), which contain the remains of

Lama's, and incense sticks burning. From here, if you look

from left to right, you can see virtually the whole

Himalayan mountain range - including Mount Everest - very

clearly. We didn't stop for long, just enough to exercise

our feet and have a quick chat and marvel at the view.

Before very long we were on our way to Shigatse via Tingri

and Lhatse. We thought that

we had hired the range rover to ourselves, but to our

disgust, the driver stopped and picked up a Chinese soldier,

despite us urging him not to do so. From this moment we fell

out with the driver. The other thing that really pissed us

off was when we drove near to Mount Everest between Tingri

and the Shegar checkpoint (where our passports were checked

again), and saw it towering above all the over mountains

about 130 miles (80 km) miles away. It had a name long

before the British called it Everest: the Tibetans and

Sherpa tribes call it Chomolungma (Mother Goddess of

the World). We wanted to stop the car and get out and sample

the view - but the driver would not stop. We all started to

lose our temper with him and l could see this driver was

going to get short shrift when we stopped at Shigatse.

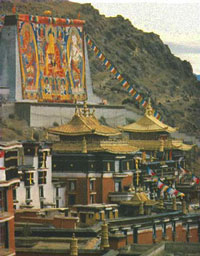

The

Tashilhunpo monastery, Shigatse, Tibet.

We arrived in

Shigatse (12,700 ft/3900 m) late one afternoon on April 26th

1986. We pulled up in the centre of the town at a crossroads

near the impressive Tashilhunpo monastery. I remember

looking out of the window of the range rover and seeing some

Tibetans from the Kham tribe in eastern Tibet, who wear

distinctive red tassels in their long hair, sitting on their

horses, one of whom had a huge sword around his waist. They

were looking on when the range rover pulled up, and we got

out, unloading our rucksacks onto the dusty road. We had

already planned how we would deal with the driver, and l

went up to him and passed him the money for the journey

through the window. We gave him roughly what the bus fare

would have been from Khasa to Shigatse. The guy freaked out.

He obviously thought that he could get a $100 or more off

the three of us (or something similar) for the journey. We

simply paid him the money and walked off, leaving him

shouting at us. I noticed the Kham horsemen looking on

amused. Thus, we began

a 16 day stay in Shigatse, not leaving the town until May

13th. The town is in the centre of a small, heavily

populated river plain near the Yarlung Zangbo (Brahmaputra)

River. After Lhasa, it is the second most important trade

centre in Tibet, as it is on the ancient caravan route that

once linked Tibet to Nepal and Kashmir. The town is the

traditional seat of the Panchen Lama (which means "Great

Scholar"), who once ruled about 4,000 monks in the monastery

of Tashilhunpo (founded 1447). The monastery was founded by

a disciple of Tsongkhapa Genden Drup, later recognised as

the 1st Dalai Lama. We stayed in

the Tibetan quarter at the Tenzin Hotel, which is opposite

the ruined Shigatse Dzong (fort). When l first saw

it, l thought it was a just large hill covered in rubble

(like the Dzong at Lhatse). We were shown old

photographs that showed the Dzong. It was quite clear

that the Chinese had just blown it off the side of the hill,

just like all the others. It was once the residence of the

Kings of Tsang and later the governor of Tsang. Pictures

dating before 1959 (when it was destroyed), show an

impressive structure similar to the Potala Palace in Lhasa.

We spent many

days on the roof of the Tenzin Hotel from which you can get

a good view of the town. It's also a good place to meet up

with other travellers and exchange stories about Tibet. I

think it was this hotel that had the worst toilets l have

ever seen in my life - simply a bare room with five or six

holes in it. Everyone just piles in, drops their pants and

sits above a hole. The first time was the worst, as since

its the only place to have a shit you just have to get on

with it. Below you, and visible through you legs, is another

room - packed with a very large mountain of excrement. It

was some poor persons job to clear this out - and l bet is

wasn't the local Chinese - It seems the plumbing system did

not come with China's "peaceful liberation" of Tibet

! After arriving

in Shigatse, l quickly started to regret not being able to

speak Tibetan - as none of them could speak English. The

only words l really learnt were the basic ones such as the

Tibetan greeting Tashi Delek, Kale Shoo

(good-bye) and Thoo Jaychay (thank you). Shigatse was a

town notorious for it's rabid dogs, packs of which would

roam the outskirts feeding off anything they could eat. We

were given simple advice - keep you distance but be armed

with a study stick and be prepared to kill if you have to.

Thus, l was amused to read the warning in the current

Lonely

Planet

guide: "Watch out for Dogs !" One of the worse diseases

you can get is Rabies, and that's the last thing you can

afford to catch in a remote area of Tibet at least 300 miles

from the nearest airport. I didn't have travel insurance so

l was very wary of these animals. On one occasion l saw them

eating a dog by the side of the road. Chris got into a tight

spot with some of them one day, but quickly managed to

dispatch one with a swift kick to the head. Apparently the

Chinese had gone around slaughtering them from time to time

(on justifiable public-health grounds), but this caused

great upset to the Tibetans, who of course are strong

believers in reincarnation. Although l

never became ill in Tibet, l would recommend travel

insurance in case you do. A German friend of ours became ill

in Lhasa with hepatitis. The first problem you have if you

don't have insurance, is how to pay the bill at the hospital

when your admitted. Our friend was taken to the People's

Hospital in Lhasa, where we visited him. The standard of

health care was very good, but foreign nationals were

charged up to six times what the locals were. If you don't

have travel insurance (or sufficient funds on you on) you've

got problems if the illness is serious. If you need to be

flown home (as our friend was), then it's left to your

embassy to get you out. The best way to avoid these problems

is to always follow advice - whether it's about altitude

sickness or hepatitis - and common sense - don't drink out

of rivers (or wash) which people use for sewage, or worse,

industrial waste. And of course, be careful of what you eat

! The Tenzin

hotel is quite big with large dormitory style rooms. It had

a friendly atmosphere and there was good food available

nearby. Nearby is then the Tashilhunpo monastery - then the

seat of the 10th Panchen Lama, and outspoken critic of the

Chinese regime, who died in suspicious circumstances in 1989

(i.e. the Chinese are thought to have poisoned him). In

1964, he declared that one day, Tibet would be free and the

Dalai Lama would return in glory as their leader. He was

effectively put under house arrest, and kept in Beijing,

visiting Tashilhunpo only under strict Chinese control.

The monastery

is surrounded by a huge wall, and immediately to enter the

main gate you get a grand view of the complex. It has a

large building - clearly visible from some distance - on

which huge paintings (or Thangkas) are displayed on

religious days. I was astounded when l entered the Maitreya

Chapel, thought by some to be one of the most impressive

sites in Tibet. Inside is a huge 86 ft (26 m) gold-plated

Maitreya, made in 1914 under the auspices of the 9th Dalai

Lama and completed in 1918 by over 900 artisans and

labourers. After walking in through a small door you are

confronted by a the huge feet of Maitreya who is sitting

serenely in the lotus position, with a huge turquoise ring

on one of his fingers. It is decorated with more than 300 kg

of gold, and covered with precious stones. On the walls are

more than a thousand images of Maitreya against a red

background. In this

monastery, l also saw the buildings where monks lived in

isolation, reputedly for periods ranging from six months to

a year. Here they learn the skills of mediation. In one

building you could see some windows were partly blacked out,

others were completely shut out to the daylight. The monks

inside have no contact with the outside world, and the rooms

are built in such a way, so that food and water can be left

without any contact being made. Along with Lee and Chris, l

wandered around exploring the monastery largely

uninterrupted. It is relatively intact compared with other

Tibetan monasteries, having survived most of the repression

of the cultural revolution. I also walked most of the

Tashilhunpo Kora with Lee - which is a circular path around

the monastery, and takes about an hour to complete - armed

with a stick to deal with the wild dogs. Even here, l notice

that the Lonely

Planet

recommend you "keep some stones at the ready". The presence

of rabid dogs prevented us from completing the trip.

Everywhere in

Shigatse, l went l found Tibetans warm and friendly - eager

to invite you in to their houses and give you a cup of the

initially foul-tasting butter tea. When l first went to

India, at first l found their tea (chai) hard to get

used to - very strong with loads of sugar in it. But l

developed a taste for it and ended up loving it. But with

butter tea it was a lot harder. Watching the making of

butter tea doesn't endure you to drinking it. The tea is

mainly made from the butter and milk of a Yak. This is all

mixed in huge dollops in a large pan to produce the tea

which Tibetans drink feverishly. I didn't develop a habit

for it, and l found it difficult when l was in a front room

of Tibetan house, being constantly offered a refill on the

cup every time l drank out of it. But that's the Tibetans

for you - for they are a polite and hospitable people.

One thing l

noticed that drives them into a state of ecstasy, was if you

produced a picture of the Dalai Lama. This we had been told

in Kathmandu. One of us had such a picture, and when

Tibetans saw it they would pass it around and bless

themselves with it. I later regretted not bringing a huge

bag full of photos just to hand out to them - though l later

discovered it was very dangerous for a Tibetan to be caught

in possession on such a photograph. I know now that the

Chinese police would have probably given us a beating if

they had found us showing Tibetans our picture of him.

Anyway, it was given away to a Tibetan family who were very

friendly towards us. We also went to

a Chinese disco (or rather gatecrashed one). Walking through

Shigatse late one night, we heard disco music coming from a

modern building which looked like a college near the

monastery. But it was surrounded by a high fence with a huge

gate. We soon climbed over it and barged our way in and

upstairs to the "disco". I noticed that it was full of young

Chinese youths (who never seemed to socialise with the

Tibetans). We walked into this huge sports arena just as the

Bony M track The Rivers of Babylon was playing. Both

sides of the hall had tables running up along the walls with

thermos flasks in them (containing tea). The men were

dancing with the men and the women were dancing with the

women. As we walked in, they all just looked at us with a

"what the hell are you doing here" stare. We promptly turned

around and walked out, laughing to ourselves as we jumped

back over the fence again. I also

attempted to get my rucksack repaired in Shigatse, which had

been badly holed by the mice in Tatopani. I found a Chinese

woman working on the street with her sowing machine,

repairing some clothes. I showed her all the holes in the

rucksack, and we agreed a price. Later that day, l went back

and picked it up. I should have checked that she had done

all the repairs. She hadn't. I immediately took it back to

her, and as l approached, l tried my best not to be angry. I

showed her the holes she hadn't stitched up, and she

repaired them. When she handed back the rucksack, l just

walked off, leaving her shouting at me. What a cheek l

thought, her thinking l would pay twice for the same

job. In India and

Nepal, there is little or no contact with women. In

contrast, l found Tibetan women to be very friendly. Once,

walking down a street in Shigatse, two women walked passed

me who were selling Turquoise stones. One of them grabbed my

hand and pointed to the beautiful jewellery made up of the

stones she was wearing around her neck, and as rings on her

finger. I politely turned down the request to buy some, as l

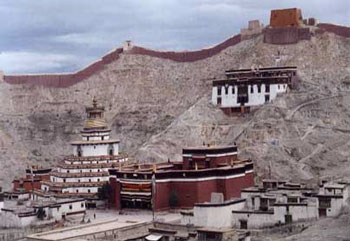

knew l didn't have enough money. On May 13th

1986, we left Shigatse for Gyantse a two hour bus drive away

(55 miles/90 km). After a short bus journey we arrived in

this small town distinctive for it's huge Kumbum

Chörten (one of the largest in the world), the Pelkor

Chöde monastery and it's own Dzong (fort) on a large

hill - last destroyed by British artillery in 1903. The

buildings date from around 1440. At 13,000 ft (3950 m) its a

bit higher than Shigatse. It's also the least

Chinese-influenced of Tibetan towns, and said to be worth a

visit for that reason alone. The Kumbum

Chörten is an impressive structure that rise over four

symmetrical floors and is surmounted by a gold dome that

rises like a crown over four sets of eyes that gaze serenely

out in the cardinal directions of the compass (see

pictures). You walk in a clockwise route up through all four

floors of the Kumbum taking in the chapels that line the

walls. It is quite clear that the Chinese have destroyed

parts of the Kumbum Chörten and the once 14 monasteries

that made up the Pelkor Chöde monastery. The central

image within the main chapel is of Sakyamuni, who is flanked

by the Buddha's of the past and the future. Around the

chapel are murals which display many of the

Bodhisattvas. The Kumbum

Chörten (extreme left), Gyanste, Tibet. We stayed for

four days until May 17th. The Chörten was very

impressive and l spent a whole day up in the Dzong (with

Lee, Chris and a German friend, Günter), after a local

Tibetan gave us the keys to to get in. The top of it also

has panoramic views of the Nyang Chu valley, and it is the

best place to view the Kumbum Chörten and the Pelkor

Chöde monastery. The Tibetans may have been able to see

the British army led by General Younghusband advancing from

some distance (like with the Chinese later), but they never

had the weapons these modern armies did. Apparently the

Dzong fell after just one day of siege leaving 300 Tibetans

and 4 British soldiers dead. The Tibetans had regarded the

Dzong as impregnable, and there was said to be a prophecy

that if it was captured then Tibet would be defeated. The

British promptly marched on Lhasa without further incident.

Gyantse is a

very small town - more a village really. We stayed at the

Tibetan Gyantse Hotel, which had an excellent kitchen, where

we eat our first decent food since leaving Kathmandu.

PREVIOUS ISSUES | WEB LINKS PAGE | READER'S COMMENTS | BACK TO FLAME ARCHIVE HOME |INDEX OF ISSUES 1-10

"In

1986, a new influx of foreigners arrived in Tibet. The

Chinese began to loosen restrictions on tourism, and a

trickle of tour groups and individual travellers soon

became a flood . . . For the first time since the Chinese

takeover, visitors from the West were given the

opportunity to see first hand the results of Chinese rule

in Tibet".

"When

the Chinese allowed the first tourists into Tibet in the

mid-1980's, they came to a devastated country, Most of

Tibet's finest monasteries lay in ruins; monks who under

a recent thaw in Chinese ethic chauvinism, were once

again donning their vestments, cautiously folded them

back to display the scars of "struggle sessions"; and the

Tibetan quarter of Lhasa, the Holy city, was now dwarfed

by a sprawling Chinatown. The journalist Harrison

Salisbury referred to it as a "dark and sorrowing

land".

On

religious days huge paintings (or Thangkas) are

displayed, as shown in the picture. Inside one

of the Chapel's is a huge 86 ft (26 m)

gold-plated Maitreya, made in 1914 under the

auspices of the 9th Dalai Lama and completed in

1918 by over 900 artisans and labourers. It is

decorated with more than 300 kg of gold, and

covered with precious stones.

Picture from http://perso.club-internet.fr/pchanez/Images