PREVIOUS ISSUES | WEB LINKS PAGE | READER'S COMMENTS | BACK TO FLAME ARCHIVE HOME |INDEX OF ISSUES 1-10

PREVIOUS ISSUES | WEB LINKS PAGE | READER'S COMMENTS | BACK TO FLAME ARCHIVE HOME |INDEX OF ISSUES 1-10

Co-editors: Seán Mac Mathúna • John Heathcote

Consulting editor: Themistocles Hoetis

Field Correspondent: Allen Houglande-mail: thefantompowa@fantompowa.org

The 1381 Poll Tax rebellion

Seán Mac Mathúna

|

John Ball and the Peasants' Revolt |

My Good Citizens: Things will never go well in England - no shall they ever - until all things be held in common, and the lords are no greater masters than ourselves - John Ball, one of the leaders of the 1381 revolt (along with Wat Tyler, above), who was executed in 1381 The bridge over the River Ravensbourne at Deptford bridge has seen three major rebellions pass over it: The first of which was the Poll tax revolt in 1381, when Wat Tyler, the radical priest John Ball and Jack Straw led 60,000 of people down from Blackheath Hill across the bridge at Deptford Broadway and up the Old Kent Road into London in 1381.13 Ball is described by Christopher Hampton in A Radical Reader as a "poor priest", who was preaching "his revolutionary creed of equality" for at least 25 years before the rebellion in 1381. In 1366, for example, he was brought before Archbishop Langham of Canterbury and forbidden to preach; that in 1376, an order was made for his arrest as an excommunicated priest, and that he was imprisoned several times. At the time of the uprising in 1381, he was in prison in Maidstone, Kent. He was one of the earliest liberation theologians, advocating justice for the poor. At this time, the people of England were nothing more than serfs bonded to the land. The Poor Laws at the time were noted for their harshness as they divided the people into "study beggars" and the "undeserving poor". This was the time of Norman feudalism when England was little than a theocracy ruled by Kings who believed they ruled by divine right of God. One of John Ball's sermons was recorded in Froissart, Chronicles 1, pp640-641, which is reproduced in A Radical Reader:

The killing of Wat Tyler - court version 'TILL EVERYTHING BE MADE COMMON' The rebels had first gathered on around the mound and ancient assembly point known today as Whitefield's Mount. This used to be called Wat Tyler's Mound, as this was the place where he and other revolutionary leaders gathered to speak to the assembled protesters. As Blackheath Common had been used for Church revivalist meetings in the 18th century by both Wesley and Whitefield, it was decided to rename the mound after him.14 Gale speculates that the Wat Tyler's Mound may have been in remote antiquity a prehistoric Gorsedd (Great Seat). As with similar sites in London (such as Kennington Common and Parliament Hill), people had the right to hold public meetings. Presumably, it was here that other revolutionaries such as Jack Cade and the Cornish rebel Michael Joseph also spoke. According to Christopher Hampton writing in A Radical Reader: The Struggle for Change in England 1381&endash;1914, Tyler had demanded at Smithfield: That there should be only one bishop in England and only one prelate, and all the lands and tenements now held by them should be confiscated, and divided among the commons, only reserving for them a reasonable sustenance. And he demanded that there should be no more villeins in England, and no serfdom or villeinage, but that all men should be free and of one condition . . .(Anonimalle Chronicle) After marching up to London and executing the Prime Minister (the Archbishop of Canterbury) and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the rebels marched on the Strand and burnt down the Savoy - not before throwing out the Poll Tax records into the street and burning them. However, Tyler was later stabbed during a meeting with the King by William Walworth, and later dragged to Smithfield's and executed. Soon afterwards, Ball and Straw were also executed, and hundreds more are believed to have been executed in the aftermath of the rebellion. Ball's last words were: Fellow-citizens, whom now a scant liberty has relieved from long oppression, stand firm while you may, and fear nothing for my punishment, since I would die in the cause of the liberty we have won, if it is now my fate to die, thinking myself happy to be able to finish my life by such a martyrdom. After the rebellion was over, the rebels were told: Oh miserable men, hateful both to land and sea, unworthy even to live, you ask to be put on an equality with your lords! You should certainly have been punished with the vilest death, if we had not determined to observe the things which had been decreed towards your messengers. But because you have come in the character of messengers you shall not die at once, but shall enjoy your life that you may truly announce our answer to your fellows.

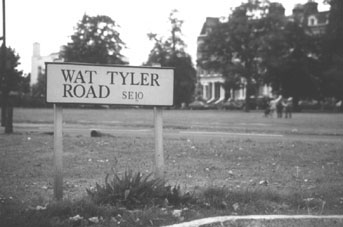

Picture by David Somerset, 1997 Wat Tyler is only remembered by Wat Tyler Road on Blackheath Common (see above). Walworth, however, had part of London named after him - Walworth in South London. The knife that stabbed him is presently in the Masonic Fishmongers Hall near Southwark Bridge in the City of London. Another of Deptford's famous revolutionaries was Thomas Whyche, the parish priest who was burnt at the stake in 1362 for being a Lollard - these were priests whose only crime was often that they had translated the Bible into common English. He is remembered in a plaque in Deptford Church. The struggle for democracy in Britain began with Wat Tyler's revolt in 1381 - it would take almost 500 years for the people to gain the right to vote - a process which begun in 1832 and was only completed in 1928 when - thanks to the collective efforts of the Chartists and the Suffragettes - when women and men were fully franchised. However, despite centuries of struggle, Britain is still without an elected head of state, a written constitution or a proper Bill of Rights. © 1998

|

|

PREVIOUS ISSUES | WEB LINKS PAGE | READER'S COMMENTS | BACK TO FLAME ARCHIVE HOME |INDEX OF ISSUES 1-10 |

|